ARTISTS

PRESS RELEASE:

Until the Paint Sets Haran Kislev & Rubi Bakal

Dual Show at Zemack Contemporary Art

Opening Reception: Thursday, October 30, 2025, at 8:00 PM

Exhibition Text by Max Salman

Painting is an act of time.

It begins at the moment of touch and ends only when matter surrenders- when the paint finally sets.

But between these two moments, everything unfolds: memory, fear, and the fragile faith that this touch might leave a mark.

In Until the Paint Sets, Haran Kislev and Rubi Bakal examine the space between construction and survival, between matter and spirit. Both work with the idea of “home”- not as a physical space, but as a lingering memory, as testimony to the one who returns again and again to a place that no longer exists.

Haran Kislev, an artist born in Kibbutz Be’eri who survived October 7th with his wife and two kids, has painted new works in the last year.

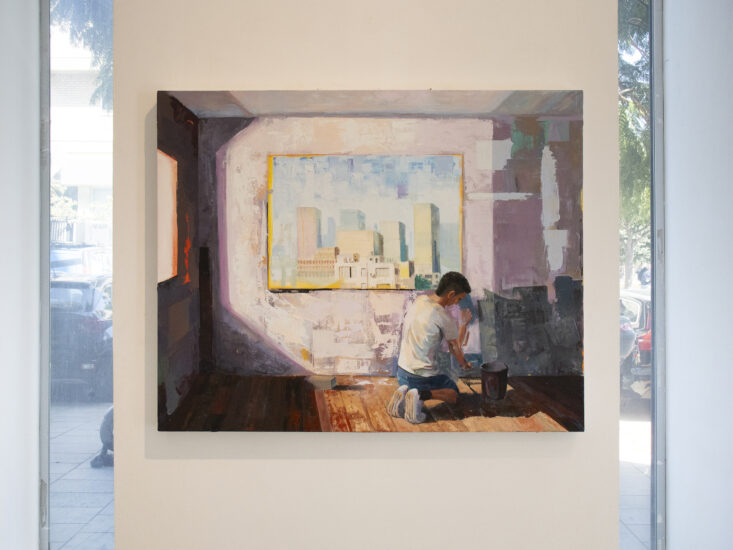

Rubi Bakal in his first exhibition at Zemack expanded on his series that documented hostage families painting, renovating and patching damaged walls in home settings.

For Kislev, paint is a liquid charged with anxiety, an attempt to hold on to memory a moment before it slips away; for Bakal, paint is a material of craft, a residue of action.

Both work within time- laying down layers, witnessing how the wall, like the body, absorbs and remembers.

Until the Paint Sets is not merely a waiting- it is an understanding that painting is a process without end. When the material sets, memory has already been inscribed within it. The walls speak in the language of color, in the tongue of traces.

—

Painting is a paradox of matter and belief: it demands faith in the image, yet exposes its material truth. In Until the Paint Sets, two painters trace the fragile line between matter and imagination, between physical and spiritual craft. Their works approach painting not as illusion but as index- as Charles Peirce described it: a mark that points to presence, a trace of what has been. This very call for belief echoes Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s wartime cry in The Little Prince: when the Pilot draws for the Little Prince, it is at once a game of imagination and of faith- a request to once again see the world through innocent, wondering eyes.

Haran Kislev confronts paint as a living medium, as liquid. In his works resides a material anxiety- the conflict between painting and its own limits, between the image and the abstract. Painting, for him, contains a crucial background: memory. It holds onto memory a moment before it dissolves. Within that tension lies its truth- painting as a tool for survival, an attempt to live inside chaos. No longer a prophetic instrument, it becomes a kind of historical ledger of memories, where everything is recorded. The “landscape” and the “home” in his works are not mimetic but emotional- constructed from shards of recollection that reappear again and again in the figure of one who cannot, or will not, forget. The act of painting becomes an act of faith, a request: paint me something that still believes in life after- something drawn from life itself. The absolute and abstract planes of color reach toward a light not yet seen, emerging from deep suffering, from sorrow that becomes an echo of Exupéry’s faith in the power of imagination amidst ruin; Kislev reflects on the impossibility of living and on the ongoing pain of present trauma- yet at the same time, on the necessity of imagination and creation as emblems of hope.

Rubi Bakal, by contrast, turns the index into both method and subject. His paintings- ranging from simplified to figurative series- are not representations of the world, but residues of its making: a perception of the labor of painting itself. Like wall painters of another era, he sources his own pigments, blending oils and minerals until matter becomes an extension of the hand. This chemistry is a kind of knowing: to understand how color behaves on a surface is to inherit a lineage of makers, each with their own secret craft. Yet while house painters labor for utility, Bakal’s purpose is contemplation- he imitates the act of painting itself, which by its nature holds an impossibility, for it can never truly be repeated. His wall paintings are, paradoxically, still lifes: paintings of surfaces, images of the very face of painting. They ask how a medium born to imitate can ever become true testimony- and in that question lies their subversion. Each layer is both icon and scar, a wall of a home rebuilt not from material, but from gesture.

Together, Kislev and Bakal build a shared landscape of construction. One sculpts with paint from the ruins of the home, thus rebuilding it; the other studies through paint the craft that allows its building. Their dialogue transforms the exhibition space into a site of construction and repair. The walls bear the traces of others- workers, painters, survivors- each engaged in the quiet art of mending a broken “home.”

In Until the Paint Sets, painting is nothing but Haran Kislev & Rubi Bakaltestimony. It carries the mark of the past- covered, yet refusing to disappear. In the end, the paint sets and the walls harden- they are like the scars of life, insisting on being seen. And yet, within that persistence, the viewer may find not despair but a subtle faith: that the act of looking, of creating, of touching the surface again and again- might itself be the way home.